ADDRESS

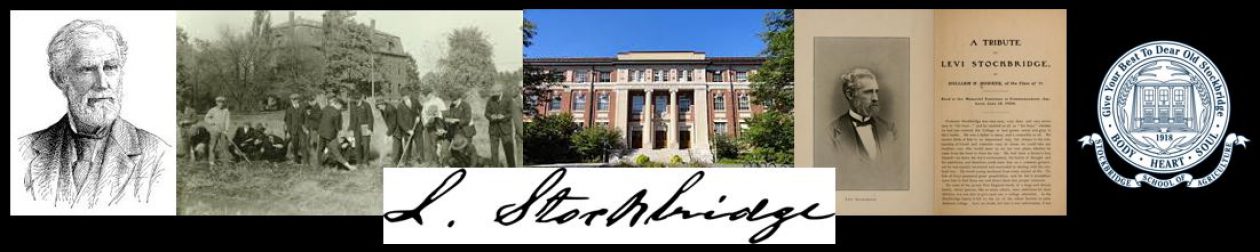

ACCEPTING FOR THE TRUSTEES THE PORTRAIT OF PROFESSOR LEVI STOCKBRIDGE

Presented to the College by the Alumni June 17, 1913

By William H. Bowker, class of 1871

Member of the Board

Mr. Toastmaster and Members of the Alumni:

This portrait of “Prof Stock”, as we familiarly called him, is a truly speaking likeness. It seems as if he were here earnestly speaking to us; as if he were saying, “Boys, that is the right thing to do”. The artist, Mr. Child, has been extremely successful in catching the soul of his subject. It was painted from a photograph; Stockbridge would have regarded it as a waste of time to sit for a portrait, but I am told that the artist knew him personally and had seen him in spirited debates in town meeting. It was in debate that Stockbridge appeared to best advantage. There you appreciated his ability, his droll humor, his common sense and his clear manner of expression.

Stockbridge loved this college. It was not his alma mater, but it was in part the work of his brain and hand. He was influential in establishing agricultural education in this country, and when the Morrill act was passed in 1862 he immediately became active in starting an agricultural college in this State and in locating it in Amherst. Soon after it was located he became farm superintendent, later professor and finally president. His influence was always helpful, especially with the student body. He was the hero of the student of my time for the reason that he was extremely human and sympathetic. As has been said of him, he was “a father confessor and an ever present help in time of trouble.”

He was not only influential in the internal development of this institution, but he was extremely anxious to have the College carried to the people. If he were living today he would take an active interest in the Extension department. It is claimed by the University of Wisconsin that university Extension Service originated in that state, but evidently Stockbridge had this kind of work in mind long ago, although it was not called Extension Service until recently. It should be remembered that in the foundation of our Board of Agriculture in the early fifties, in which Stockbridge had a part, the act provided for the appointment of “agents” to go about the state in the interests of better agriculture, which is a form of Extension work.

Professor Stockbridge typified in a measure the kind of education we are giving here, vocational education combined with practical training. He believed a man was trained in some degree who could do any one thing well, hold a plow or make a plow. He felt that we had held up too long as our ideal the Websters, the Phillipses – the orators, scholars and writers, placed manner before matter, forgetting that men at their benches could think and would think, perhaps as clearly and sanely as men who were trained to express themselves in polished English; thus, the sooner we recognized trained men in all walks of life, the better it would be for society. Be it said to the credit of the University of Wisconsin, a leader in progressive educational ideas that she is recognizing merit and accomplishment wherever she finds it without regard to college degree or previous schooling. Suppose our great eastern universities should grant degrees, or some sort of recognition to men high up in the arts and crafts as well as men distinguished in letters or in business, would it not help to ameliorate the social conditions and “to lessen stratification in society?” as Professor Ross of the Wisconsin University expresses it.

STOCKBRIDGE’S PLAN FOR THE DIFFUSION OF PROPERTY

The first President of our College, Judge French, said in his first report (1866):

“Republicanism has undertaken in America to recast society into a system of equality. Its purpose is to diffuse education and property among all the people; to give as nearly as possible every child an even start in the world. Therefore, in deciding on a course of study and discipline for an agricultural college, we must ever remember that we live under a republican and not an aristocratic government.”

That was also Stockbridge’s idea. He was thoroughly and sincerely democratic. He had no love for an aristocracy, and especially no love for a plutocracy. IN one of his class lectures he broke out one day with the remark, “no one should hog it all, no one has the right to more than a stated amount of property – for example, a million dollars.” Some years after when reminded of this remark he was asked how he would regulate the size of fortunes, he said;

“I would regulate them through the probate court, and if a man’s estate was found by official expert appraisal, to be worth more than the allotted sum, the excess should go to the State.”

When it was suggested that this would be unconstitutional, he remarked “True, but men make constitutions and they can unmake or modify them.” When it was suggested that it would tend to destroy ambition and nullify initiative and effort he said in effect:

“I would give every man a chance to make by lawful mans, not by ‘lawful steal’ (as he termed stock watering(1)) as much as he could during his lifetime, but he must give it away before he died. He should only be allowed to will away, or leave for the probate court to pass upon, a sum not exceeding a stated maximum amount, which should be the maximum prize.”

It was suggested that if this plan were adopted, the Astor scheme (2) of giving outright the larger part of the estate to the oldest son would still prevail and thus great fortunes would be handed on and increased. He replied substantially;

“Under my plan that scheme would be extremely hazardous. Suppose a man amassed ten million dollars, and knowing that he could will but a million, he would give outright before he died nine million dollars to his only child, a son, but before the son had disposed of it he was knocked on the head, then only one million would go to the son’s heirs and eight million would revert to the State.”

Stockbridge felt that the effect of such a plan, properly safeguarded, would not lesson ambition within reasonable limits but would tend to lessen greed, and eventually to make an inherited plutocracy impossible. He believed men, like boys, should have prizes to work for and should play the game according to the rules, but that the rules should be modified to meet new conditions. Stockbridge was what might be termed a “limited individualist” (3). He would give the individual every opportunity up to a certain point, and then, as he expressed it, “I would clip his wings.”

“And why not? If our universities find it wise to fix a maximum prize, and our boys in their games find it necessary to place a handicap on the strongest player, to equzlie conditions and to make the game fairer and more interesting, why not, in the game of life, have some kind of bar to the crafty and unscrupulous, to the end that the prizes shall be more fairly divided and more widely distributed.”

TRUSTEESHIPS

Perhaps someone can tell us if Stockbridge was in favor of trusteeships. It would seem that Trusteeships (except for women and minor children) where fortunes are tied up indefinitely and managed by superior talent, are a greater menace to society than were the original fortunes when managed by the men who made them; for the men who made them had latitude and frequently exercised it for the greatest good of the greatest number. Trustees have little or no latitude.

Our forefathers came here to establish a new order of things, among others to inaugurate a better system for the diffusion of property. To that end they abolished primogeniture and unlimited entailment of property. They little dreamed, however, of the growth and power of trusteeships, lodged in individuals or in trust companies and insurance companies. They little dreamed of fortunes running into hundreds of millions of dollars willed in trust to an infant child, to be turned over to the child, or his heirs twenty-five, fifty or seventy-five years hence, minus a small part of the income. Stockbridge lived to see in the inheritance tax a partial step toward the better distribution of great fortunes. It is quite possible that the inheritance tax and the income tax will be superseded by a more drastic system for the diffusion of property.

Levi Stockbridge, self-taught, was a wise teacher, a useful citizen, and a true friend. He left his stamp on this College and upon hundreds of loyal students. As representing the trustees and on behalf of the College, I accept this life-like portrait of him. We are sincerely grateful to the alumni for it. We promise to keep it and cherish it as we cherish and honor his memory.

(1) Watered stock is an asset with an artificially-inflated value. The term is most commonly used to refer to a form of securities fraud common to corporations.

(2) John Jacob Astor was the nation’s first multi-millionaire who transferred his wealth to his oldest son, William Backhouse Astor, when he died in 1948. His estate made up of many New York City properties was valued at $20,000,000.

(3) Stockbridge held the “limited individualist” belief that society’s greater good would best be served by the state’s limiting individual wealth to one million dollars in order to preclude the existence of an inherited plutocracy. Such ideas were consistent with his membership in the pro-labor, pro-farmer, anti-monopolist Greenback Party. In his 1904 eulogy, Bowker speculated that had Stockbridge been born in the twentieth century, “he would have become, in the best sense of the word, a socialist.”